Janapadas

Changes were underway in India during the period of the Late Bronz Age and the Iron Age. The Vedas were written, and ancient Indian culture, society, and religion were all being transformed. One of the major transformations took place in the political organization of the subcontinent – janapadas were forming and altering the way people lived.

The Vedic period in India is traditionally dated to between 1500 and 500 BC. This period succeeded the Indus Valley Civilization, and in turn was succeeded by the Maurya Empire. It was a culturally and religiously significant time, as it was during this era that the Vedas, the oldest sacred texts of Hinduism, were being composed. Politically speaking, the Vedic period, specifically towards the end of it, saw the formation of various Indian states in the north that are known as janapadas. Over time, these states would develop into 16 major states, which are collectively known as the mahajanapadas.

Etymology of Janapada

The word ‘jana’ may be literally translated to mean ‘people’, or ‘ethnic group’ / ‘tribe’, by extension. ‘Pada’, on the other hand, means ‘foot’. Therefore, taken together, ‘janapada’ may be taken to mean ‘foothold of a tribe’. During the Vedic period prior to the formation of the janapadas, the Indo-Aryans of India were living in tribes called janas. These tribes were semi-nomadic, though they later adopted a sedentary way of life.

By settling permanently in a certain area, a tribe could claim possession of it, which in turn would give the tribe a geographical identity. The relationship between tribe and land may be seen in the fact that areas were often named after the tribe that settled on them. This new lifestyle required a new political organization, which was important so as to ensure that the tribe could maintain possession of the land. Thus, the janas were replaced by janapadas.

Evolution

Literary evidence suggests that the janapadas flourished between 1500 BCE and 500 BCE. The earliest mention of the term "janapada" occurs in the Aitareya (8.14.4) and Shatapatha (13.4.2.17) Brahmana texts.

In the Vedic samhitas, the term jana denotes a tribe, whose members believed in a shared ancestry. The janas were headed by a king. The samiti was a common assembly of the jana members, and had the power to elect or dethrone the king. The sabha was a smaller assembly of wise elders, who advised the king.

The janas were originally semi-nomadic pastoral communities, but gradually came to be associated with specific territories as they became less mobile. Various kulas (clans) developed within the jana, each with its own chief. Gradually, the necessities of defence and warfare prompted the janas to form military groupings headed by janapadins (Kshatriya warriors). This model ultimately evolved into the establishment of political units known as the janapadas.

While some of the janas evolved into their own janapadas, others appear to have mixed together to form a common Janapada. According to the political scientist Sudama Misra, the name of the Panchalajanapada suggests that it was a fusion of five (pancha) janas.Some janas (such as Aja and Mutiba) mentioned in the earliest texts do not find a mention in the later texts. Misra theorizes that these smaller janas were conquered by and assimilated into the larger janas.

Janapadas were gradually dissolved around 500 BCE. Their disestablishment can be attributed to the rise of imperial powers (such as Magadha) within India, as well as in the Northwest of South Asia by foreign invaders (such as the Persians and the Greeks).

Nature

The Janapada were highest political unit in Ancient India during this period these polities were usually monarchical (though some followed a form republicanism) and succession was hereditary. The head of a kingdom was called a (rajan) or king. A chief (purohita) or priest and a (senani) or commander of administrating the army who would assist the king. There were also two other political bodies, the (sabha) thought to be a council of elders and the (samiti) a general assembly of the entire people.

Monarchies and Republics

There were two types of janapadas – monarchies and republics. Monarchies were ruled by rajas, or kings who had absolute authority. In such janapadas, the king was regarded to be divine, and was the owner of the land. As the people were working on ‘his’ land, they were thus required to pay taxes, the rate of which was generally 1/6 of the produce. To ensure that these taxes were paid, tax collectors were appointed, and a royal standing army was established.

Janapadas that were republican in nature may also have rajas, although these were not the same as those belonging to monarchies. In republican janapadas, the raja was a title given to a chief who presided over the janapada’s Assembly, and the office is not hereditary. Real power was in the hands of the Assembly, which consisted of the representatives of the tribes, or the heads of the families.

Significant Mahajanapadas

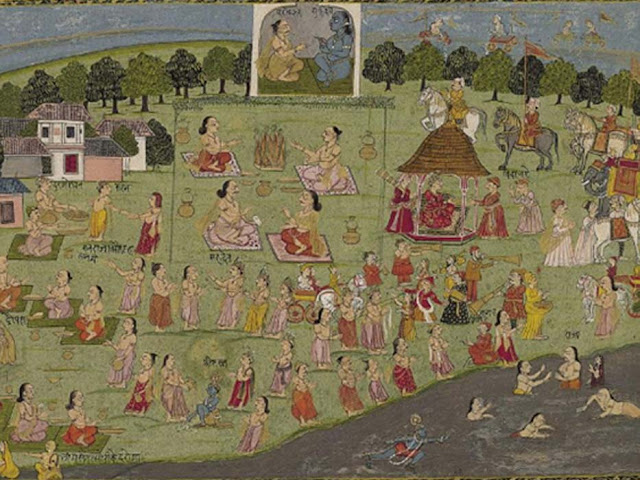

Over the course of time, the more powerful janapadas conquered the weaker ones, and eventually, 16 mahajanapadas, or ‘great janapadas’, emerged. The mahajanapadas are important in the history of India as they are the historical context in which the two great Hindu epics, the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, were composed. The mahajanapadas are mentioned in both these literary works. For example, some of the mahajanapadas, including Magadha, Anga, and Gandhara are mentioned in the Mahabharata.

Additionally, the mahajanapadas also provide the social and political context in which Jainism and Buddhism emerged. Nevertheless, the mahajanapadas are mentioned only in passing by the texts of these religions, although the list differs from one text to another. In the Anguttara Nikaya , a Buddhist text, for instance, a list of the 16 mahajanapadas is given, which is as follows: Kasi, Kosala, Anga, Magadha, Vajji (or Vriji), Malla, Chedi, Vatsa (or Vamsa), Kuru, Panchala, Machcha (or Matsya), Surasena, Assaka, Avanti, Gandhara, and Kamboja.

The cities and villages

Some kingdoms possessed a main city that served as its capital. For example, the capital of Pandava's Kingdom was Indraprastha and the Kaurava's Kingdom was Hastinapura. Ahichatra was the capital of Northern Panchala whereas Kampilya was the capital of Southern Panchala. Kosala Kingdom had its capitacapi at Ayodhya. Apart from the main city or capital, where the palace of the ruling king was situated, there were small towns and villages spread in a kingdom. Tax was collected by the officers appointed by the king from these villages and towns. What the king offered in return to these villages and towns was protection from the attack of other kings and robber tribes, as well as from invading foreign nomadic tribes. The king also enforced code and order in his kingdom by punishing the guilty.

The boundaries of the kingdoms

Often rivers formed the boundaries of two neighboring kingdoms, as was the case between the northern and southern Panchala and between the western (Pandava's Kingdom) and eastern (Kaurava's Kingdom) Kuru. Sometimes, large forests, which were larger than the kingdoms themselves, formed their boundaries as was the case of the Naimisha Forest between Panchala and Kosala kingdoms. Mountain

ranges like Himalaya, Vindhya and Sahya also formed their boundaries.

Administration

The janapadas had Kshatriya rulers.Based on literary references, historians have theorized that the Janapadas were administered by the following assemblies in addition to the king:

- Sabha

- An assembly of qualified members who advised the king and performed judicial functions. In the ganas or republican Janapadas, they also handled administration.

- Paura

- Paura was the assembly of the capital city (pura), and handled municipal administration.

- Janapada

- The Janapada assembly represented the rest of the Janapada, possibly the villages, which were administered by a Gramini.

Some historians have also theorized that there was a common assembly called the "Paura-Janapada", but others such as Ram Sharan Sharma's disagree with this theory. The existence of Paura and Janapada itself is a controversial matter.

Indian nationalist historians such as K. P. Jayaswalhave argued that the existence of such assemblies is evidence of prevalence of democracy in ancient India. V. B. Misra notes that the contemporary society was divided into the four varnas (besides the outcastes), and the Kshatriya ruling class had all the political rights. Not all the citizens in a janapada had political rights. Based on Gautama's Dharmasutra, Jayaswal theorized that the low-caste shudras could be members of the Paura assembly. According to A. S. Altekar, this theory is based on a misunderstanding to the text: the term "Paura" in the relevant portion of the Dharmasutra refers to a resident of the city, not the member of the city assembly. Jayaswal also argued that the members of the supposed Paura-Janapada assembly acted as counsellers to the king, and made other important decisions such as imposing taxes in times of emergency. Once again, Altekar argued that these conclusions are based on misinterpretations of the literary advance. For example, Jayaswal has wrongly translated the word "amantra" in a Ramayana verse as "to offer advice"; it actually means "to bid farewell" in proper context.

Interactions between kingdoms

There was no border security for a kingdom and border disputes were very rare. One king might conduct a military campaign (often designated as Digvijaya meaning victory over all the directions) and defeat another king in a battle, lasting for a day. The defeated king would acknowledge the supremacy of the victorious king. The defeated king might sometimes be asked to give a tribute to the victorious king. Such tribute would be collected only once, not on a periodic basis. The defeated king, in most cases, would be free to rule his own kingdom, without maintaining any contact with the victorious king. There was no annexation of one kingdom by another. Often a military general conducted these campaigns on behalf of his king. A military campaign and tribute collection was often associated with a great sacrifice (like Rajasuya or Ashvamedha) conducted in the kingdom of the campaigning king. The defeated king also was invited to attend these sacrifice ceremonies, as a friend and ally.

New kingdoms

New kingdoms were formed when a major clan produced more than one King in a generation. The Kuru (kingdom) clan of Kings was very successful in governing throughout North India with their numerous kingdoms, which were formed after each successive generation. Similarly, the Yadava clan of kings formed numerous kingdoms in Central India.

Cultural differences

Western parts of India were dominated by tribes who had a slightly different culture that was considered as non-Vedic by the mainstream Vedic culture prevailed in the Kuru and Panchala kingdoms. Similarly there were some tribes in the eastern regions of India, considered to be in this category. Tribes with non-Vedic culture specially those of barbaric nature were collectively termed as Mlechha. Very little was mentioned in the ancient Indian literature, about the kingdoms to the North, beyond the Himalayas. China was mentioned as a kingdom known as Cina, often grouped with Mlechcha kingdoms.

List of Janapadas

Vedic literature

The Vedas mention five sub-divisions of ancient India:

- Udichya (Northern region)

- Prachya (Eastern region)

- Dakshina (Southern region)

- Pratichya (Western region)

- Madhya-desha (Central region)

Puranic literature

The Puranas mention seven sub-divisions of ancient India:

- Udichya (Northern region)

- Prachya (Eastern region)

- Dakshinapatha (Southern region)

- Aparanta (Western region)

- Madhya-desha (Central region)

- Parvata-shrayin (Himalayan region)

- Vindhya-prashtha (Vindhyan region)

Sanskrit epics

The Bhishma Parva of the Mahabharata mentions around 230 janapadas, while the Ramayana mentions only a few of these. Unlike the Puranas, the Mahabharata does not specify any geographical divisions of ancient India, but does support the classification of certain janapadas as southern or northern.

Buddhist canon

The Buddhist canonical texts primarily refer to the following 16 mahajanapadas ("great janapadas"):

- Anga

- Assaka

- Avanti

- Chetiya

- Gandhara

- Kamboja

- Kashi

- Kosala

- Kuru

- Machchha

- Magadha

- Malla

- Panchala

- Surasena

- Vajji

- Vamsha

The Jain text Bhagavati Sutra also mentions 16 important janapadas, but their names differ from the ones mentioned in the Buddhist texts.

Comments

Post a Comment